‘An easy target’ Sex traffickers often seek out people with a history of substance use, feeding their addictions to trap them in a cycle of debt. Experts say the very institutions designed to support people in recovery can fail to protect them.

GBH News / NPR

Phillip Martin and Jenifer B. McKim

Bruce Bemer made no secret of what his money could buy. The wealthy Connecticut businessman admitted to police and the FBI that he purchased sex from drug-addicted young men. But Bemer strenuously denied a far more serious charge: knowingly participating in a human trafficking operation.

Three months ago, the Connecticut Supreme Court agreed with the 68-year-old defendant — ruling unanimously that a lower court failed to prove he was aware of the trafficking operation that provided the young men he paid to perform sex acts.

Far more boys and young men are victims of commercial sexual exploitation than previously understood, a GBH News investigation has revealed, and the Connecticut case shows how difficult it is for prosecutors to hold alleged abusers accountable. It also points to how drug addiction and treatment facilities present key recruitment opportunities for predators, anti-trafficking advocates say.

It is believed that the traffickers who provided Bemer with young men operated for almost 30 years, according to a Danbury detective who was involved in the case. Robert King and William Trefzger preyed on emotionally damaged and troubled youth, often using their drug addictions to gain trust before turning them into sex workers.

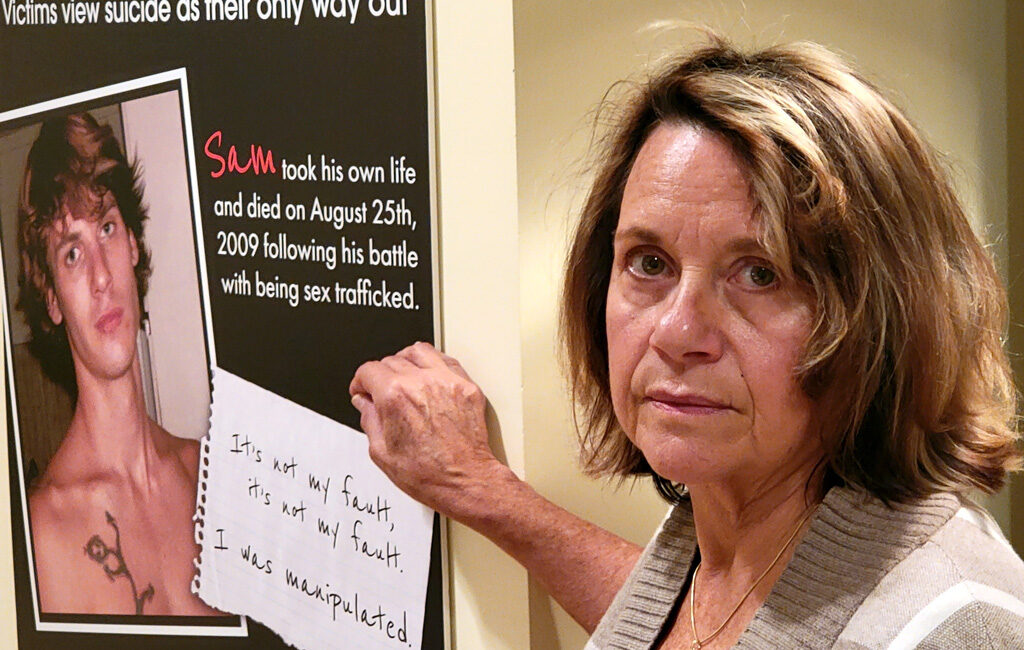

The Connecticut high court’s decision shocked many in the state who have followed the case, but perhaps no one more than Lin Marino, whose son, Samuel, was one of the trafficking victims from whom Bemer purchased sexual acts.

“It removes any justice that we may have received for our son,’’ Marino told GBH News. “It was devastating news.”

Samuel died in a car crash in 2009 while being pursued by police after a carjacking, according to a police report. But his mother and others are convinced he took his own life by purposely crashing the car he was driving.

Samuel Marino took chances. He excelled in snowboarding and loved nothing more than BMX biking. He broke a lot of bones doing what he loved. And after graduating Tolland High School in 2001, Samuel, who had a learning disability, built barns for a living, putting further strain on his body.

Lin Marino said he was often in pain. That led him to OxyContin, then heroin. Through tears, his mother recalled asking Samuel to leave the house.

He went to several rehabilitation centers, she said.

“Little did we know that every time he would come out of a rehab facility, they were waiting for him to readdict him so they could traffic him,” she said.

Samuel stayed at a Liberation House facility in Stamford for nearly six months, court records show. Nobody at the organization’s corporate headquarters could be reached for comment.

It was outside the rehab center in Stamford that Samuel met with Robert King and William Trefzger.

“Sam didn’t have a chance,” his mother said. “Robert King picked him up out of his first rehab and told him he was going to be his sponsor, pretended he was a friend, and Sam’s friend. And all the while he was readdicting my son, over and over — every time my son tried to get clean — so that he could use him for his own profit, to sex traffic him.”

For years, Marino and her husband, Michael, now deceased, were unaware of what had happened to their only son. But in 2017, Marino quickly put two and two together after reading a story in the Hartford Courant about three men who were arrested for trafficking boys and a handwritten note at the scene that included the words, “It wasn’t my falt, It wasn’t my falt. It wasn’t my falt.”

“When I read the note that victim number 13 had written, and it was still in King’s trailer, I screamed because I knew that was my son’s note. I knew my son’s writing,” she said. “I knew his lack of spelling.”

Nine days before his death in August 2009, he had checked himself into Danbury Hospital and told doctors he felt “guilt, worthlessness and a wish for punishment,” according to medical records shared by his mother.

“We thought he committed suicide because he was ashamed of his drug habit,” she said, “when I think in reality, he was ashamed of being trafficked.”

King, who was still pretending to be Samuel’s friend, attended his funeral and came to the Marino family’s home for Thanksgiving dinner.

Marino said King also tried to solicit one of her nephews, a heroin addict, into his network.

She said the depth of King’s deception was shocking. “He set up a Facebook page dedicated to Sam: ‘Always to be remembered,’ and constantly posting pictures of Sam.”

In 2019, Bruce Bemer was convicted by a jury of four counts of patronizing a prostitute and one count of accessory to trafficking in persons. The judge handed down a 20-year sentence for which Bemer would have to serve 10 years. But he avoided prison altogether. After posting bail totaling $1.3 million, he was remanded to his Glastonbury home under house arrest while he appealed his conviction. Bemer declined a request for an interview through his attorney.

Robert King, 56, of Danbury, Connecticut, the purported leader of the sex trafficking ring, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit human trafficking and was sentenced to state prison in June 2019. In exchange for testifying against Bemer, his sentence of 20 years was suspended by the trial judge after he served four and a half years in prison. King was released several months ago with time served. Through his lawyer, Chris Duby, he declined to comment on this story.

A third defendant in the Connecticut case, William Trefzger, 77, pleaded guilty to patronizing a trafficked person in February 2018. He entered into a plea deal. In exchange for his testimony against King and Bemer, his 10-year sentence was suspended after one year served and 10 years of probation.

Trefzger, who admitted his role in targeting young men with drug addictions, became the first person convicted under a 2013 Connecticut human trafficking law. But he was never called to the stand by prosecutors to testify against King or Bemer. Telephone messages left at Trefzger’s home in Westport went unanswered.

King’s drugs-for-sex enterprise began to unravel in January 2016 when workers at a group home in Torrington noticed him coming and going at all hours and signing a resident out of the facility.

Dan Trompetta of the Danbury Police, now retired, was the lead detective in the case. He told GBH News that he was contacted by a state probation officer who said King was prostituting one of her clients. She said King gave her client drugs and made him perform sex acts.

Seasoned investigators in court testimony said they were shocked by the extent of what they discovered and the impact on victims and their families. Investigators testified in the criminal trial that King checked at least one victim out of Connecticut Valley Hospital, a state-run psychiatric facility. The young man was sexually exploited and then returned to the facility, police said.

Trompetta said King would also find young men at group homes, sober houses, shelters and on the streets. He asked some of them to stay with him in a trailer park in Danbury, where he supplied them with a steady stream of drugs and alcohol.

“Most of them have had problems with substance abuse prior. Some had recovered, and King destroyed that,” Trompetta explained in an email. According to psychiatrists and depositions taken in civil hearings all of the young men targeted by the human trafficking ring suffered severe psychological problems including Samuel Marino. “He was a manic depressive, and I think this made him an easy target for this sex trafficking ring,” said his mother.

King’s trailer is situated off a two-lane road populated by industrial sites and abandoned work sheds. Police staked out the house for months. They made a move in June 2016 after an FBI agent spotted King chasing a young man who ran from the trailer, then hauling him back inside.

That led to a search warrant and King’s arrest, Trompetta explained.

Standing in front of the box-shaped home, Joel Faxon, a New Haven attorney representing some of the young men who were exploited in the Bemer case, said the virtual captivity King used on his victims was the closest thing he had seen to indentured servitude.

“He would load up the van with young men and bring them to a destination where they’d have to perform sex acts in exchange for cash, and then the cycle would continue,” Faxon said. “They’d have a drug debt, and then they’d have a rent debt, and then they’d have a room and board debt, and a food debt — and they’d ultimately all have to perpetually be paying him off while they were trapped here.”

The main beneficiary of the Connecticut trafficking ring was Bruce Bemer, prosecutors say, who had a reputation for getting what he wanted. The Glastonbury businessman built his career on inherited wealth. He owns a petroleum company, a motorcycle dealership and the New London-Waterford Speedbowl.

Bemer got the young men he wanted through intermediaries. One of these men agreed to speak exclusively with GBH News, but only under a pseudonym because he feared “what Bemer’s money can buy.” He said he served as a debt collector and a “fixer,” arranging for individuals to meet Bemer at various locations, including at his Glastonbury plant after hours.

Sitting in a restaurant just off Interstate 84 in East Hartford, “Scott” said he met Bemer at a popular outdoor gay cruising site in the 1990s that has long been paved over by roads and remade by gentrification. Scott said Bemer decided to have others procure his partners after he was robbed by a man he had met at the site.

“He gave me a description of what he liked. I just interviewed them,” Scott told GBH News. “A lot of them, to do what they did, they had to neutralize their inhibitions.”

Scott would bring young men desperate for money to Bemer’s Glastonbury factory after hours. “It was always done at night when everybody’s gone, so nobody can witness anything or say anything. And then I walk out of the room.”

When police raided Bemer’s office, they found Coca-Cola bottles printed with the names Samuel, Zach, Dustin and Matt — all young men Bemer paid to perform sexual acts.

Scott said Bemer later turned to Robert King to supply young men.

“I met Robert King through Bemer at his plant in Glastonbury where he was bringing the boys,” Scott said. ”Personally, I didn’t like Bob King. He was very arrogant. He was able to furnish the young men who patrolled around — boys that were kind of astray, who were on drugs. I didn’t do that.”

Recruiting at recovery sites

Traffickers are known to find victims at treatment sites. Addiction centers, mental health facilities and sober houses often lack adequate oversight by the agencies tasked with keeping young people safe, anti-trafficking advocates and officials say.

“Traffickers target vulnerable people in our society, and that is what you see with such young men who are coming out of rehab,” said Lillian Agbeyegbe, community engagement manager for Polaris, a national anti-trafficking organization based in Washington, D.C.

Polaris found that more than 2,200 people — or about 15 percent of those who called its National Human Trafficking Hotline between Jan. 1, 2015, and June 30, 2017 — said that drugs or alcohol had been used to induce them into prostitution.

The true number is likely higher because the data only includes information that was volunteered by callers, Agbeyegbe said. A 2016 study funded by the Justice Department found that out of 1,000 youth who acknowledged participating in the sex trade, 84 percent used drugs and alcohol and 36 percent were males.

“Substance use disorder is often one way victims are brought into or kept in a trafficking situation,” said Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, whose office for years has made human trafficking a top-tier priority. “Unfortunately, we’ve seen traffickers target vulnerable people struggling with addiction who have nowhere to go, no one to rely on, and feel they have no other option to survive.”

Ten years ago, Boston-based clinical social worker Steve Procopio collected data showing that most male survivors of sex trafficking were recovering addicts.

“I did a series of focus groups, and when it came to the topic of drugs or alcohol, they noted that that was the primary way their offenders would start grooming them into trafficking,” Procopio said. “And with this particular group, a lot at that time was crystal meth, which is very addicting.”

Attorney Faxon, who built his reputation representing plaintiffs in Connecticut’s Catholic Church abuse scandal, said stigma keeps many victims in the shadows. Faxon said most of his clients are heterosexual men who struggled with drug addiction and mental illness, and are afraid of disclosing what happened to them.

“It’s difficult to come forward,” he said. “They know that their frailties and difficulties that they’ve had in life are going to be exploited by the lawyers for these traffickers.”